Nino Rollo

selection of works

biography

A child prodigy, a man always prone to excess, an anarchist opposed to everything and everyone, a man of refined

understanding and great curiosity, an impulsive writer, in love with life and at ease with death.

It may be for these very reasons that Nino Rollo, sculptor and draftsman, does not have a significant place in the history of art, and yet he was a strong personality and created a body of work that remains to a large extent unexplored and unappreciated.

It may be for these very reasons that Nino Rollo, sculptor and draftsman, does not have a significant place in the history of art, and yet he was a strong personality and created a body of work that remains to a large extent unexplored and unappreciated.

Born at Lequile, in the province of Lecce, on October 27, 1942, he finished elementary school at the age of eight.

After attending art college in Lecce, he graduated from the Magistero d'Arte in Naples in 1959. The Naples of the fifties, a lively,

flourishing and dynamic city, was a fundamental human and cultural experience for Rollo, a place where he studied a great deal and had

the opportunity to meet outstanding figures in the world of art and culture. It was a time of research and discovery. In fact he had

teachers like the sculptor Ennio Tomai and the art historian Raffaele Mormone and attended the lectures of the writer Vasco Pratolini.

He also had the chance to frequent the studios of artists like Romolo Vetere, Aldo Calò, Augusto Perez and Vincenzo Gaetaniello. It was

in the latter's studio that he encountered the work of Brancusi for the first time in a photographic reproduction of the Spirit of Buddha.

During the same period he was able to see Henry Moore's work at the anthological exhibition staged at Valle Giulia in Rome.

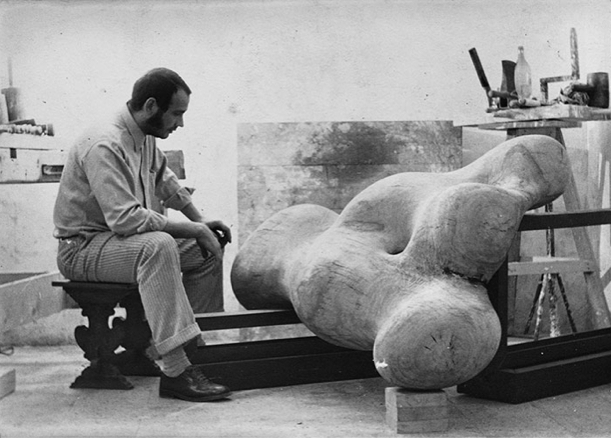

Nino Rollo in his workshop at Poggiardo (Lecce), 1969. Photo archives of the Fondazione Nino Rollo

Returning to Lecce after graduation, at the age of just eighteen, he began to teach at the Istituto d'Arte di Poggiardo.

The same year the experience of his first trip to Paris, and of visiting the Louvre, Brancusi's studio

and the Musée de l’Homme, marked a decisive turning point in his development.

The Neapolitan period also proved fundamental for his learning the traditional techniques of the art, such as woodcarving

in Gaetaniello's studio or the polishing and patination of cast metal in Tomai's. Manual skills were always vital to Rollo, as was contact with

and understanding of the material. This manual ability was the means that allowed him to attain an intimate connection between thought and form,

between himself and his material. Learning about materials was not just a matter of technique but indispensable if he were going to be able to hold

a dialogue with nature, in other words to create sculpture.

He had learnt to work iron at school and in the workshops of his artisan friends, using it at the beginning of his career,

associated with wood or stone, in works that were influenced by the sculpture of Aldo Calò. In the sixties he worked mostly with wood, large

trunks, as much as two or three meters long or even more, of walnut, oak, eucalyptus and chestnut. He polished the surfaces carefully and

sometimes covered them with silver or gold leaf, or with aluminum paint, and later on with patinas created by mixing earths, graphite and wax

as in the tradition of ethnic African sculpture.

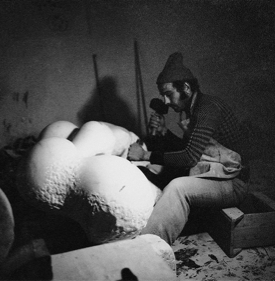

Nino Rollo in his workshop at Poggiardo (Lecce), 1974. Photo archives of the Fondazione Nino Rollo

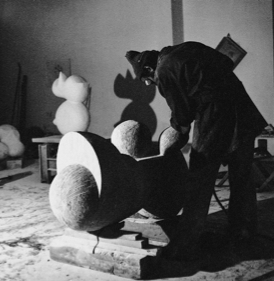

Nino Rollo in his workshop at Poggiardo (Lecce), 1976. Photo archives of the Fondazione Nino Rollo

Nino Rollo, detail of his hands with a small sculpture. Lecce, 1980. Photo by Francesco Spada

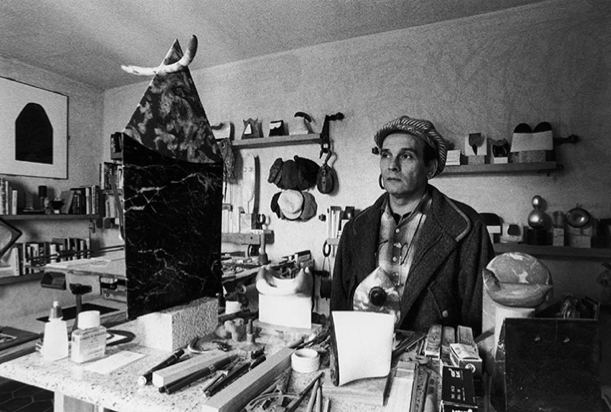

Nino Rollo in the workshop on Via Birago in Lecce, 1980. Photo by Francesco Spada

He had an almost animistic feeling for natural elements, an awareness that induced in him a sense of

humility and respect for the trunk or block that he was going to sculpt.

The choice of taglio diretto, of working the material directly, by hand, was not just one of technique.

It was very much in line with his character. Not given to half-measures, he was against any compromise in life and in art. His quest for

the “absolute“ was almost ferocious. He claimed to be a peasant and to be working for a sculpture that “has its roots deep in the earth but

its gaze fixed on heaven.” He felt himself to be an anarchist: “Sculpture does not advance by evolution, but by revolution. It is a drastic

break with the past, subversion, contradiction.”

A Cagli, in the Marche, where he taught from 1970 to 1973, he carved his first sculptures in stone in the workshop of a

craftsman who worked with alabaster and colored onyx.

His love of stone was unreserved, just like his character. He declared that his real teachers were limestone, marble

and granite and described himself as a scultore pietrante, a sculptor who worked stone and became stone, proudly laying claim to a

symbiosis with the material, the result of a long process of learning.

Solitude was a necessary dimension of Rollo’s artistic research, something he sought and loved, especially in

the years that followed. An isolation due to his geographic location—he had in fact returned to Lecce—but also to the rather sleepy cultural

milieu, so often to be found in the provinces, caught up more in a dream of the past than in the urgency of the contemporary world.

And yet Rollo’s choice to stay in the South was conscious and resolute. He had a love-hate relationship with the land of his birth

that often led him to burst out in fierce tirades, but he also felt a deep kinship with its people.

Nino Rollo in the studio on Via Birago in Lecce, 1990. Photo by Pierluigi Bolognini

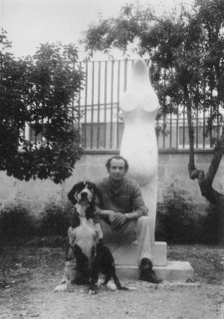

Nino Rollo with his dog Taras in the garden on Via Birago, Lecce, 1980. Photo archives of the Fondazione Nino Rollo

Nino Rollo in the garden on Via Birago in Lecce, 1990. Photo by Pierluigi Bolognini

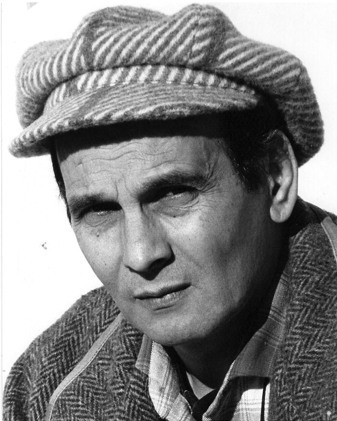

Nino Rollo, 1990. Photo by Pierluigi Bolognini

From one of his trips to Pietrasanta, in the summer of 1982, he came back with a box of sheets of semiprecious stone. The color of those stones (the blue of sodalite and lapis lazuli, the green of malachite, the red of jasper or the pink of rhodonite) had enchanted and excited him and this marked the beginning of a new direction in his research into materials.

He spent long hours—entire days, when he was not sculpting, and part of the sleepless night—shut up in his studio,

reading, writing, drawing, taking notes, studying.

His partners in this research were texts and images of art, without limits of time or place, writings on aesthetics,

philosophy, criticism. He read about poetry, music... He was curious about anything and avid for everything.

He nourished himself on these authors, conversing with them. And his constant companion was stone,

“which gives me splendid advice and is almost my only friend.”

In this space were born the sculptures that he would call relics of the cosmos, monstrance-sculptures, silentiary sculptures, sound sculptures,

hanging stones, sculptures in freedom, sculptures with feathers, stones of silence.

Although suffering from heart trouble, he never spared himself. He died of lung cancer in Paris on January 26, 1992. He had not yet reached the age of fifty.

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|